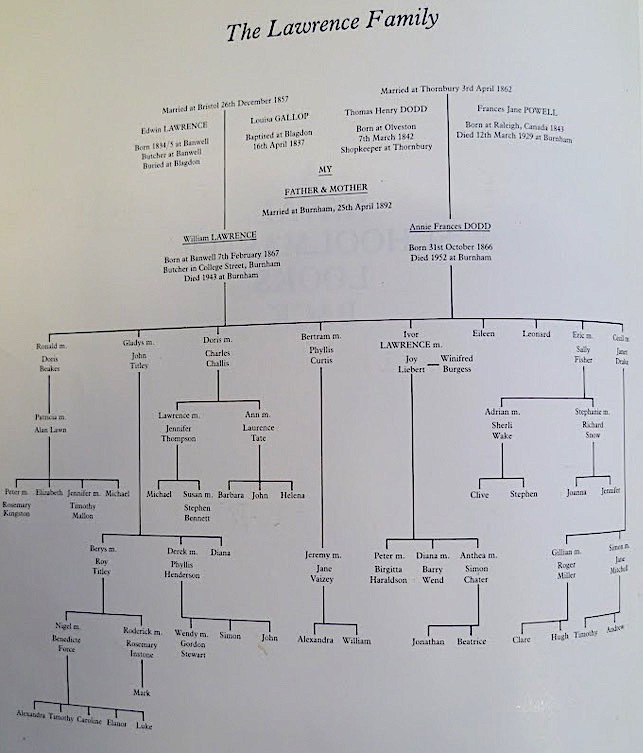

From ‘ A Naval Schoolmaster Looks Back’ by Ivor D.Lawrence – Extracts

This extract gives an interesting picture of life in Burnham during the first decades of the 20th century through the eyes of a young boy.

CHILDHOOD 1901 – 1913

INTRODUCTION

Summer 1985. Joy and I stood outside No 31 College Street, in Burnham-on-Sea, one of our frequent visits there, to spend a day with Eric and Janet. Alterations were in progress; my old home was being converted into offices…

We were jamming the doorway. A man came up from behind us. ‘Can I help you?’

I began to tell him that this was where I was born in 1901 at the turn of the century. He looked interested, and I continued: ‘Over that door at the back of the shop was a tile which they must have recently removed. It had a message stuck in its adhesive mix. I put it there when I was about 10 years old. It was the third tile from the left over the door’.

‘Why don’t you come in and look? There is a pile of those tiles at the back.’

My mind immediately entered and shot up the stairs to the family living quarters above…it would take some time. I thanked him and declined. Musingly I led Joy away and up Victoria St, back to Janet’s again.

I BEGIN, 1901, APRIL 10th

As I write my memoirs I am comforted by the thought that I have no general public in mind, thus eliminating a time schedule, or any quantity target or commerce factor.

I was born in 1901 into, at that time, a family of four, two elder brothers and two sisters. I suspect that the presiding doctor was Dr. Berry who lived in an imposing house down the Berrow Road and who attended the birth in a pony and trap.

It was the year in which Queen Victoria died; I missed being in her reign by just three months. Burnham had also just ceased to be a port although pleasure steamers continued to come over from Cardiff and Barry in South Wales. The Boer War was just drawing to its close and the new century was opening with optimism. My age would always be just one year short of the current year. It was April, a good month to be born in.

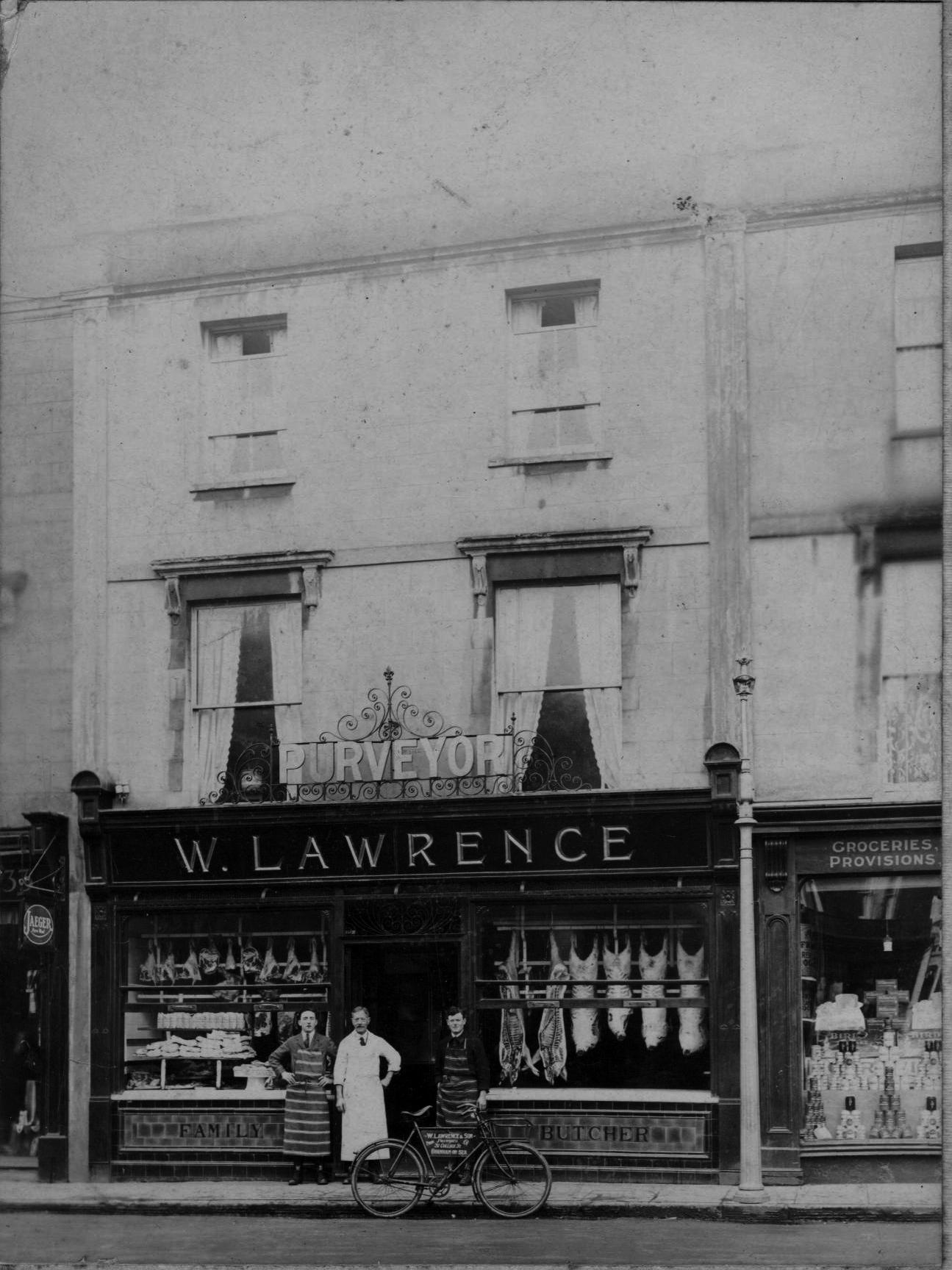

Father was a butcher (on his bills a ‘Meat Purveyor’) not a trade he would have chosen, but, in those days, a man had little choice in what he wanted to do. Grandpa had too many children, 12 in fact, to be able to be over concerned about choice. He eventually retired to a house in Blagdon, with a well in its garden from which all the water used had to be drawn up. It overlooked the lake which mirrored in its waters the slender sore of the village church on the hill above. He came often into Burnham as, apart from the shop which father had taken over, he had other property there.

I would see grandpa sitting by the fire, mostly on Mondays, in the room behind the shop, with his tall hat on his knee, a stern face framed in a fringe of whiskers from which came questions, rather sharply, with pulls on his pipe in between. A bristly kiss and I would be sent out to play.

Father was a conscientious and hardworking man, up at 5am to read a portion of the Bible, a large family one, and then down to prepare the shop, renewing the sawdust on the floor before the ‘men’ arrived. At what stage he began to bring tea up to us all I cannot recall, for there were eventually nine of us.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

ABOUT MY HOME

31 College Street, with a shop at its base, was a terraced house of three floors, with outbuildings at the back for storage, stables and a slaughterhouse. Above was a loft with access by wooden steps, a treasured venue for all sorts of games for us children. The whole was truly a butcher’s establishment where the animals ‘on the hoof’ became meat to be sold in the shop. There were, perhaps, six ‘men’, average wage £2-10s per week, 3 or 4 of whom lived on the premises reached by the back stairs….no bathroom, but then neither did the family have one. Our ‘nursery’ door separated us from their quarters and the back stairs up which our bathwater came on Sunday nights. Through our nursery window you could look opposite to the rainwater tank, about ten feet square.

At age ten, or thereabouts, I had to have my tonsils out, a regular operation in those days. The operating table was in the drawing room, the room above the shop which was normally one used on Sundays. I remember so well the moment when the chloroform was applied to my nose and the quiet authoritative voice saying count with me 1,2,3,4….at which point I had gone. Then I woke up in Mother and Father’s bed next door and was very sick, with blood mostly. I still have, in my convalescence, the hymns I then wrote, and the emotional poems about the Boer War inspired somewhat by Ron’s rendering of Dvorak’s ‘Humouresque’ which I still associate with that period.

Certainly, I have every satisfaction inn the place and circumstances of my birth…a stable home with loving parents in the little town of Burnham in Somerset…tranquil, remote, self contained.

At about this time, my brother, Leonard……..having what is now called ‘Down’s Syndrome, wandered out to the ‘back’ and fell into a vat used for curing tripe. He survived after a massive clearing up process and grew up t be a very loveable member of the family. He died in 1944 at the age of 40 at a special institution where he was a very well liked ‘guest’, very efficient as a hall porter.

No 31 was in one of the streets running down from the sea front. It faced Victoria Street which ran parallel to the sea front to the Church. From the ground floor, generously proportioned stairs, with a smooth bannister ran up to the first floor. These bannisters were much valued for their whirling slides downwards, straddle fashion, the generous height of each floor providing. good run. At the top of the first flight you turned left up a short flight to the drawing room and right into the nursery. The dating room extended the whole width of the house, that is, the width of two ordinary rooms. Another flight of stairs led up to the next floor of bedrooms, three in all with a small room for the maids. How cold it was, when, from the warm living room below we were sent away to bed up all those stairs to the cold rooms above. As the family grew and needed more room, the wall into Mr Warner’s house next door was breached and one more room for the girls was provided.

The room behind the shop served as office and dining room…’Hush, Father’s at his books’, and at 1pm we would all be sitting round a long table with Father at its head and Mother on his left serving vegetables and gravy, while Father carved. Many plate loads went out to the kitchen where the ‘men’ were having their meal, Hodgie taking it out to them.

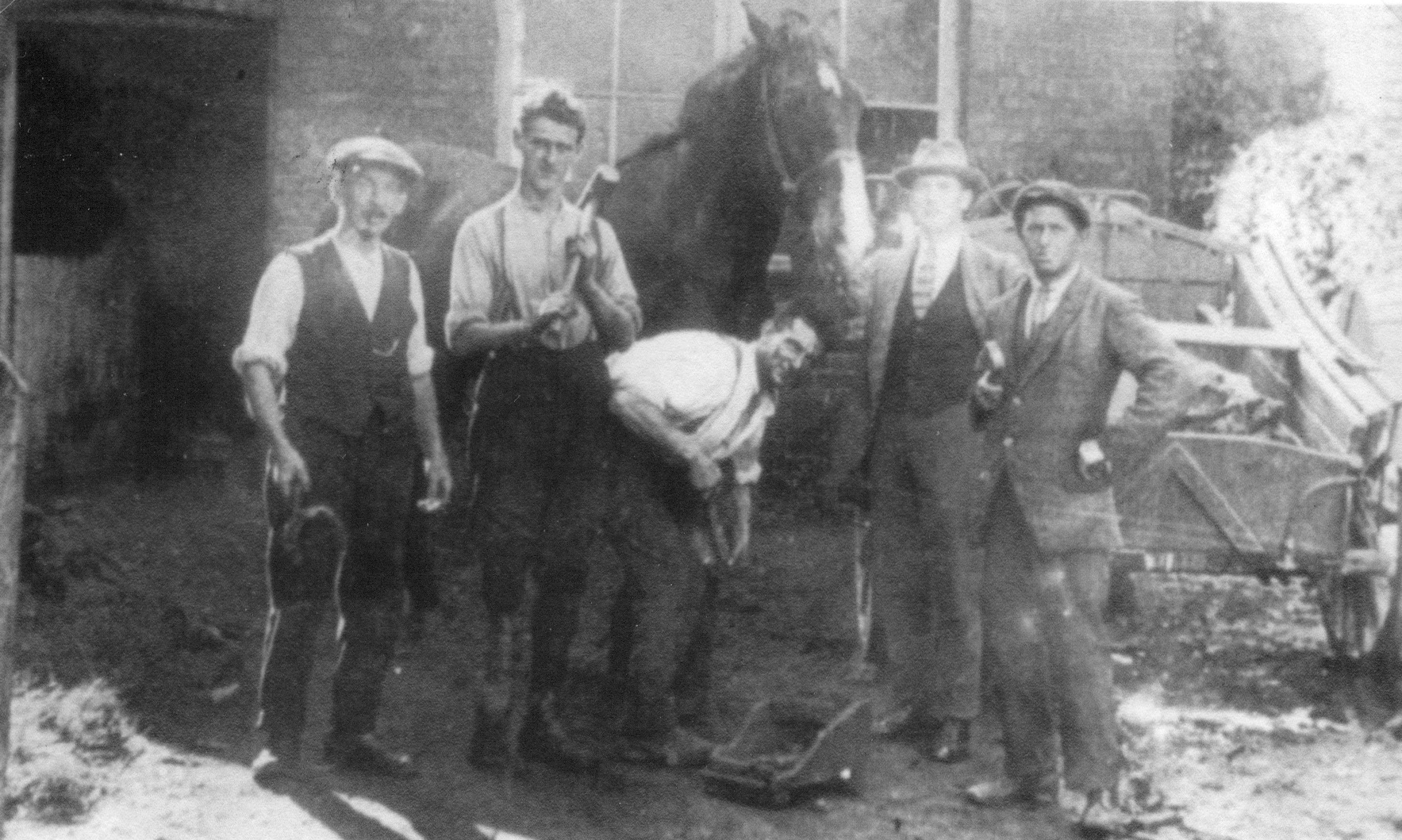

Out at the back was the ‘slaughter house’, a white tiled walled chamber with chains and pulleys reaching down from the ceiling. To reach it from the sitting room you walked down the stone flagged passage outside and through the glass door on the left; to reach, in turn, on the left, the bicycle shed, the salting chamber (barrels of bacon and hams),no fridges I those days, and, to the right, the kitchen, wash house, sausage machine house, boiler and coal shed. ‘Tommy’ or ‘Joe’ might be seen in the act of killing a sheep which he has just upturned on the flagstones outside the slaughter house.

Mother never liked us going out there but it was always a fascination and we were very naughty. From behind the doors of a shed on the right you could hear the snuffling of the sheep waiting their turn, or the grunting of pigs. On the left was the stables for the horses, above which was the loft. I was once missing for hours, and the police were about to be informed when I was found sitting ini the straw at the rear of my favourite horse, quiet and content.

One door down from us was No. 33, Mrs. Strevens’s dress emporium, which sold everything to do with clothing and sewing and knitting. One door up. No. 29, was Mr Warner’s grocer’s shop which often I was to visit on errands for Mother.

‘Half a pound of butter please’. Mr Warner, who had a soft spot for us despite having to rescue and return many balls appearing over his wall, would look down from above with an amused and benevolent eye. ‘Well, me young fellow m’lad…half a pound is it?’

Then he would take two wooden platters and deftly chop off a chunk of butter from a large slab.. The chopping and patting rhythm which followed never ceased to fascinate me; on the scales, off the scales, bits off, bits on, until a perfect rectangular shape of precisely half a pound was achieved. Finally, both platters deposited this miracle onto greased paper which would be folded up, over, and sealed. ‘That will be 6d sonny’. Then the triumphal return to mother sitting in the shop desk, with a sweet in my mouth, as likely as not, a favour from Mr. Warner.

Some years later I was to seek the grave of Mrs Streven’s son in Mesopotamia. He had been killed there. I found it, and took a photograph which I brought home to her.

Below Streven’s shop was the ‘tuppeny tube’, a narrow path between walls separating her shop from the precincts of the Wesleyan Church. It led to our back street, a ‘cul de sac’. There we were free to play games of cricket against the wall of Hill and Churchills and the printing establishment of ‘Patey’. As we played the double doors of the slaughter house area would be on our right with the loft above. On our left would be the many back gates of the houses whose fronts opened out into Cross Street.

Returning to College Street…above Warner’s was a shop, over which Miss Churchill presided. Here I collected my weekly ‘Gem’ and ‘Jack, Sam and Pete’ and similar publications and, at some time, conceived a pash, never revealed, for a dark haired maiden who served behind the counter. Above again, came the Post Office and then Uncle Courier’s ironmongery, with its back premises erupting behind into the very end of the cup de sac street. Here he had a large workshop in which he manufactured (literally by hand) bird scarers, which he sold and sent all over the country. They must have been quite famous.

Of the family there were ‘Girlie’, Kenneth (my contemporary and playmate) and Albert. I remember they possessed that wonder of the age, a musical box, with a roller having pins sticking up all round it, picking up tunes, a fascinating entertainer.

Across that end of College Street lived another boyhood companion, Alan Kerton, in whose back yard I often played. He went to sea at the outbreak of the 1914 war in the Merchant Service and came back, having survived the sinking of his ship by torpedo, in borrowed French clothing, a heroic figure, which determined me and two other boys to follow his example and go to sea.

Next to his house was Lloyds Bank on the corner of King Alfred Street [Alfred St / High St] and College Street, which went on for 200 yards to the sea front and the entrance of the Elementary School which I attended for six years, often making my daily journey there in leisurely fashion by rolling twopenny marbles called tooers along the gutters. Or sometimes, by bowling a hoop made by the blacksmith whose premises were at the bottom of College Street.

To that school I shall always owe a debt for its beneficial practice of initiating ‘silent reading’ during the last period on Friday afternoons, which established in me the love of books. During this period we were loaned books like ‘David Copperfield’, ‘Ivanhoe’, ‘Coral Island’ etc. I remember my nickname during these school years was ‘Buster’.

Sometimes very high tides in the winter months would bring seas over the retaining walls and down the streets like College Street in a flood, causing hurried construction of sandbagged walls outside the shops. During that period a major reconstruction of the sea front was completed with a promenade protected by a stouter sea wall. In the year in which this is written I note another major reconstruction is being undertaken.

FATHER’S ROUND

Walk down College Street, away from the sea front, or down any of similar streets parallel, and it will not be long before you find a gate which leads you across a field. One in a flat countryside of green fields, hedges, ditches, stretching for about two mies to Brent Knoll. Here the animals, which Father sold as meat, were reared, as were those bought by Mr Miles the rival butcher, who, of course, we thought not quite up to Father’s standard.

‘Fred’ or ‘Philip’ or ‘Tommy’ went out into this countryside on his special day of the week with a gaily coloured cart drawn by one of our three horses, selling meat at the farmhouse doors. We children much enjoyed being taken fr one of these rounds for the day. The doors at the back would be opened showing the joints of meat slung on hooks and there would be a meat slab and a scale pan. There was a seat high up in front which could be protected by a tarred awning when it rained, and below you the back of the horse with his docked tail and blinkered eyes.

Father had a lovely ‘round’ on Fridays lasting all day. First, in the morning, out via Edithmead to the A38 main road from Exeter to Bristol, calling at interesting farms, with long waits, while the farmer’s wife came out and bought her weekend meat. It was a leisurely operation. She would be pleased to see father and interested in the member if the family he had brought with him.

‘Be that your’n Mr Lawrence? Which one is ‘ee then – would ‘ee like an apple me dear?’ And there would be much chatter and careful choosing, and weighing on the scales and chopping on the block. Finally a large purse would emerge from somewhere below her ample skirts as Father pursed his lips and announced the weight: 4lbs 7 ops. ‘That will be 7s 6d,…well 7s to you Ma’am…lovely bit of prime beef… came from Dibbles east side of the Knoll.’

And then, out would come his capacious white canvas cash bag from his white apron pocket and a dip of the hand produced the required change, golden sovereigns conspcuous. The bag would be carefully retied and replaced and the font wrapped up, farewells said and off we would go again. At the next farm some steers were to be viewed, steers which dad had it in mind eventually to buy, at the right time and price.. ‘Hop down and open the gate sonny’ and there was a certain pride in standing holding the gate open while the horse and cart went through, and stopped for me to mount again. And then, on again, jogging along between hedges and fields, in and out of the farm yards, with much friendly talk of weather and crops at the tiny doors of Ivey covered cottages where we would linger and chat, while the chop! Chop! And sawing went on.

And I would be exploring…or stroking the sleek cats which came out daintily to pick up any tit bits dropping from the chopping block, and patting the dogs which had heralded our approach with frantic barking.

‘What do ‘ee think of they airiplanes zir?’ One of Colonel Cody’s Circus was flying over at that moment. ‘Madame, I wouldn’t fly in one for a fortune’…much laughter. ‘Keep away there I tell ‘ee!’ In a sudden shriek to her small son who had shyly approached the horses head. ‘Go on indoors now it be too cold for ‘ee.’

At the last farm, before we meet the A38, we turned around and then had a delightful uninterrupted jog all the way back the Edithmead Road to where it said ‘Fork right for Berrow’.

Presently, as prearranged, we would meet Joe on his delivery of orders round, and receive from him the latest news from the shop. We had touched the nearest point to home but were to be away all day. At mid-day we would be outside the Berrow Inn and Father would disappear inside to reappear with a pottery jar of fizzy lemonade, or ginger beer and a glass. The stopper(glass too) would be removed and the glass file. Then, exciting moment the lunch parcel would be explored, carefully packed by Mother, and out would come packets of cheese sandwiches followed by some with blackberry and apple jam fillings and, perhaps, a doughnut. For the rest of the day there would be reminders of that meal for the fizz saw to that. Periodically there would be sharp pangs behind the ears only relieved by a fizzy belch.

A little further on from the hotel was a small store shop where dad bought a bag of white flour for the horse which was all the horse was to eat during the day except for such grass as he could crop during our various stops.

The thrill of the morning subsided as indigestion and sleepiness took over and anyway, there was much steady jogging along a road with small sand hills each side, sleepy and deserted.

But then, suddenly, we stopped at a gate in a hedge from the top of which a ship’s prow figure leaned over…a painted figure of a lady in wood [see ‘The Nornen’]. Father walked in with a bucket and disappeared along a winding path to the cottage, reappearing very soon with it filled with water from a well. Into the bucket he tipped the flour, stirring it with a twig, until the lumps dissolved into white liquid.

The horse’s ears, meanwhile, would be well up in anticipation, and as soon as the bucket was in position, in would go his muzzle and the loud suction noises would begin, the level of froth sinking as he drank. The efforts to get to the last few drops were prodigious and, after the bucket had been removed, there would be the pleasant mopping up work around the nostrils, so much enjoyed by him and by me watching him.

On one occasion, I remember, as I was gently rubbing his soft muzzle and enjoying that special horsey smell, out from a gate some hundred yards ahead came teams of volunteers with 40 pounder field guns, trotting across the sand dunes for exercises on the sands. That was a great thrill and I never pass that spot without remembering it.

But now it was afternoon and we were entering the long sand-dune bordered road, windy and sandblown which, after 4 miles, ended in Brean Down and the Bristol Channel. Sleepy, my imagination wandered into scenes of scouting and Boer fights and Pathan ambushes. It would have been frightening to think of wandering away from Dad and the cart over those dunes on our left.

Later, near Brean Church, I had to set off on a special adventure. While dad attended to call group of cottages, I had to set off with a basket containing a sirloin of beef for a farm some distance in from the road. There was a white gate to be surmounted and a long cart track through two fields and some thick trees.. I did not like this part at all because of some fearsome looking geese which came waddling across to meet me, with stretched necks and fearsome beaks. I was frightened and there was nobody about. However, a run brought me to the door of the farm at last and the sight of a human being restored my spirits. The reunion with father, by another way which joined his road further towards break, was a matter for great content.

Then on we went to Mr Hickson, and, finally, to the last farm of all at the foot of Brean Down itself.

And now the return journey. Dad took special care to see everything stowed for the long drive back. We would wrap up comfortably, for evening was now coming on and we were to be homeward bound with some 7 miles to go. Here, once, we gathered a store of stones to hurl at the rabbits we saw on the dunes. We never hit one, nor expected to, but got fun out of seeing them scurrying away. Once I ket a stone slip. Out of my hand and it hit Dad on the head. It gave me a shock and I cried with remorse and the stone throwing stopped.

At the end of a straight two mile jog we turned left onto the other road back to Berrow and Burnham, inland from the dunes. Jogging down that inland road, two more farms to visit, about a mile between them…then the lamps had to be lit, candles, I think.

And the the real homing jog trot with the music and rhythm of the horses feet as dad sang ‘Rock of Ages’ and we seemed to be the only people in the world…lights in the doorway at Berrow…shadows of horse and cart mysteriously appearing from behind, catching us up and passing us…the warm shop. Windows.

The horse’s steps quickened as we neared home. And sometimes his tail would rise up high and a B flat major French horn series of notes in time with the foot beats would arise, as if he felt he ought to join in with the general euphoria.

Soon we were clattering down Victoria Street to the bright lights of the shop and to the lovely welcome…I felt heroic and a hardy adventurer to be waited on and fed…and so to the cosy sitting room and fire. Our hot dinner had been put aside for us. Eileen always shared a little of our meal and was dubbed ‘Gibby’ as he nickname because of her quaint demand ‘Gimme! Gimme!’ On those occasions. And so to bed.

THE NURSERY

The nursery was a busy room in wet weather, especially in the winter. Outside the rain would patter into the fresh water tank where we lost many of our balls.

We played ‘lodging houses’ organised by Gladys and Doris. Strings appeared criss-crossing the room with newspapers slung over, to divide the room into many compartments, each of which had its own special function. One was a tea room where we solemnly sat at tea with miniature tea sets. Another was the grocers shop with counter and scales, small bottles and packets. I think too there was a hospital ward or surgery? With red crosses conspicuous on linen and one or two nasty looking implements about.

Bath night came on Saturdays when the boiler was put on, a major operation with ready sorting of logs of wood and some coal, with the hot water having to be brought up the back stairs in buckets. A fire was lit in the nursery and Mother and Hodgie presided over the bathing of Eileen and me, being about the same age.

After the bath came ‘powder time’ an ‘opening’ portion of powder disguised in a teaspoon of raspberry jam. We hated that jam for years afterwards. Eileen would start to yell as soon as the spoon began to close on her mouth, her nose would be pinched to make her open her mouth to breath and in the spoon would go. If that dose proved ineffective more repulsive ‘liquorice’ powder was tried. Maybe we ate more meat than was good for us with little in the way of fresh vegetables, salads and fruit and too much in the carbohydrate category…buns and pasties. Certainly we fed very well if, probably, not too wisely.

When the bathing was over and the nighties were on came the warming up by the fire, before climbing the stairs to clean sheets, with the knowledge that tomorrow was Sunday.

SUNDAY

Sunday morning was late rising and a leisurely descent to the sitting room where, always we had boiled eggs for breakfast and no fire. Seldom was a fire lit in two rooms of the house at once, except on occasion of illness when doctors always insisted on bedrooms of at least 60 degrees.

On Sunday we used, as our family sitting room, the large drawing room upstairs and there the fire was lit…for that one day.

At about 10am the family prepared for Church. We all went, except Hodgie, who stayed behind to prepare the lunch waiting for us on our return. The nursery became a busy place with Gladys and Doris struggling into their high buttoned booties with button hooks and we into our starched cuffs and collars… a lot of running upstairs to the cupboards and chests of drawers for the clean linen to replace the discarded dories, to be taken downstairs for the Monday wash…the second big job for the boiler copper.

The Church bells began to ring and we were all walking up Victoria Street and just about to enter the Church door as the ‘Hurry! Hurry!’ Five minute bell broke in upon the peals. Our entry was by a side door, onto stairs which led past the vestry up to the gallery, where our family occupied one front pew looking down on the congregation in the body of the church, the choir on our lefts and, interspersed among the locals, the serried ranks of girls and boys from the numerous private schools in the area. I might, of course, have dropped into the vestry as we entered in order to don my surplice, for I was for some years in the choir.

The seats were hard and the sermon long, at least of an hour’s duration in those days. We choir boys, naturally, were bored and thought up many games while the droning went on………… During the last hymn father would pass pennies down the line for the family to put in the collection box as it came round. And, after the service, we mingled with the stream of people going up to the sea front for a pre-lunch stroll, with many pauses too chat, while the girls and Mother went back to the house to see about the dinner.

Whose day for Gran’s dinner? Mine perhaps? I didn’t like it for it meant trailing up King Alfred’s Street [sic] alone, with a covered plate of dinner in a basket…pudding on top in a basin, holding it all very carefully up to Sunny Lawn, her cottage. Gran would take it into her kitchen, unload it, carefully wash the crockery and replace it all in the basket. I would have her own special type of mint lump as a reward from her own little store, which she bought from Miss Hardwick’s sweet shop.

If we wanted horse radish at any time, and we always did when beef was on the menu, Gran had a very good patch and that would be one of the occasions for a visit to her.. Next door to her lived Mother’s special friend, Mrs Randell, the headmistress of the nursery school. Always, later, before I went away after the holidays, it was a duty to go up and say goodbye to Gran.

After Sunday dinner we would go upstairs to the drawing room where Father would soon drop off for his ‘forty winks’ while we played with our toys or read our books. Before the high tea at 6pm the whole family would go off on its Sunday walk, probably across the fields in the neighbourhood of ‘Hunt’s Pond’ where, in summer, the fields would be resplendent in a covering of buttercups, cowslips and daisies.

And then home to tea of buttered toast and slices of Mother’s rich cake with ‘touchers’ (half buns spread with jam and cream). After tea we were all called to hymn singing with Ron playing the piano and Gladys the violin; I hated to be called away from my ‘Chums’ at this point.

Then the Bells would peal out again and Hodgie would pop her head in dressed for church to say that she was off.

HALLEY’S COMET

It was about this time [1910] that Halley’s Comet came into view, not to appear again until this Christmas time 1985. All in Burnham were very excited. At the bottom of College Street was the entrance to the ‘Coronation Field’, so called as the venue for the celebration of the coronation of Edward VII. Here the people gathered to look upwards into a clear sky for the viewing, which had been announced by the Town Crier. I have only a memory of the crowds, on that occasion, wending their way down College Street, not of seeing the comet.

THE WORKING WEEK

The working week started in leisurely fashion on Monday morning working up to maximum intensity on Saturday. So the morning was spent in cleaning windows, brasses, slabs and floors, and in making up the books and bills and the delivery of the same to the customers. Very few of the regulars paid for the meat on receipt. There were those with weekly accounts, monthly accounts and even quarterly accounts. The latter would almost certainly include most of the prep schools some of whom were not diligent in paying up on time, one, in fact, running its debit account for three years. The advantage of having ready supplied playing areas, the sands, with the sea performing its useful cleaning operation regularly must have been a very helpful attraction.

Mother did much of the booking work, until, eventually, Ron came on the scene after leaving Wellington School…’She’s a monthly, hand me the ledger Son.’

father would be at his stock book and the making out of cheques in payment to the farmers. On all the stationery, hand bills, etc., was printed the shop’s motto ‘We better serve ourselves by serving others best.’ It was many years before I came to understand what it meant.

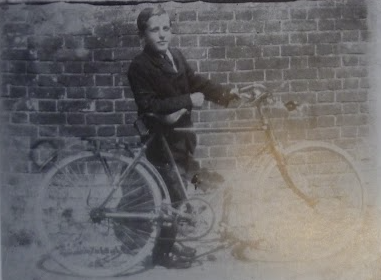

Monday, too, was a good day for Dad to cycle around the countryside to view the stock he anticipated buying and often, later on, when I had achieved my bicycle, I would accompany him.

Usually we went out to the A38 road by way of Edithmead and along to Brent Knoll, returning by way of Berrow, a route which covered most of the farmers and stock which he wanted to see.

The long and tortuous, but pleasant, chat indulged in, leading up tp bargaining, was a special art. The main subject, the sheep or steer in view, slid in as it seemed, only by accident and often deadlock was averted only by sudden change in subject…’How’s sam Dibble with his leg?’ ‘Haven’t seen ‘un lately…was told he were very poorly…they steers is worth more than 3 willie!…can’t take less than 4 a piece…Joe got 5 last week.’

I never could tell the exact moment at which a bargain was struck but dad would suddenly grab his bicycle and we were off again. ‘Did you buy them dad?’ ‘No, but they’ll do for next week.’

He was a very patient buyer and skilful at choosing the best meat, which assured him a good reputation, and, certainly, what better habitat for producing good livestock could one find than the rich grass areas around Burnham.

I can never remember seeing my parents angry, but how they kept their equanimity so consistently in that crowded household was a wonder. Mother was, of course, tied there much more than Dad and I remember far more about our cycling excursions than about the ceaseless work about the house that must have gone on.

Market day in Bridgwater was Wednesday and, of course, was worth attending.. Again, an occasion for a day out for me accompanying Dad who, as usual, would catch the train only by running the last few yards past the Somerset and Dorset Hotel, just outside the station. I think I remember the guard looking out for him and delaying the whistle until he had closed the carriage door behind him.

We would attend the cattle market in the morning and then repair to ‘Stucky’s restaurant’ for a glass of milk and a bun to ‘put us on’. And then, over to the sheep market with the sheep herded into pens. It was fun to hear the auctioneer gabbling away and to guess the precise moment when a bid was accepted, and who made the bid, and how.

I have been rambling on about the years between 1904 and 1912. I went to school at 5 under Mrs Randell; the classrooms opened out into a small lane at the back of the school on the sea front and, occasionally, I was released to join Joe at the bottom of the lane for his delivery of meat orders down the Berrow Road. I used to meet him in his cart outside Hauser’s ironmongery shop with great joy and anticipation.

Later, I was moved up to Standard I with Miss Pugsley in charge, a very efficient uncertified teacher who had a large class of small children whom she managed and taught most efficiently. Mr May, the Headmaster, used to arrange concerts every year at the Town Hall. The whole school seemed to be on stage, rising in tiers behind him, with the audience below.

I remember studying recitation under Miss Pugsley and having a bandaged hand which had been trodden on by a hob-nailed boot. I had to stand by Mr May, who was seated in a chair at the front of the stage, and recite a piece of about 12 verses which ended each with the words “I wonder why?’ ‘When mother said the other day that I must go outside and play da da da dee da da da de….I wonder why?’ That’s how it ran.

Was it about then we had great fun in the hayfields which dad owned down Edithmead Lane, just past Stucky’s house? In July, the hayfield would have its cutting and the hay would be stacked in ricks.. This was the occasion for a grand picnic at which some 90 children and adults would be invited…members of local large families. There were the Hausers, the Cops, the Pleasses, the Chants (who gave us magic lantern parties at Christmas) the Couriers, the Coxes, the Woodman’s and the Randells etc., etc.

We played rounders, and other games, and rolled in the sweet smelling hay. There was a smaller, tightly enclosed field, reached through a gap in the hedge, which always seemed rather mysterious and forbidding, attracting and yet repelling, so that finding yourself in it you hastened to get out again for it seemed dark and enclosed. There were rides on the heavily loaded wains and, as we all sat round at tea, the men drew longs swigs from large earthenware jars, full of cider.

There was the annual pageant held in the Public Gardens. I remember ‘Robin Hood and his merry men. Dad was a knight under Mr Dare (Richard Coer de Lion) and, in one year, the volunteers put up a show on a summer’s evening by lying down on their tummies, on the inner side of the hedge, and making a brave show of musketry through the hedge at the bowling green, where the enemy were presumably receiving it hot.

The park was a lovely playground for us children who often annoyed the ‘keeper’ by running on his flowerbeds, so lovingly tended. Hide and seek probably was the game that caused so much trouble; keenest and excitement took over completely. A valued refreshment constantly at harvest time available was the dropped fruit of a very old Mulberry tree, which, I believe, has only come down in recent years.

The sands, of course, was also our natural playground where we ruined our boots with mud and salt water kicking heavy soggy footballs about. Two ready made goalposts were the piers of the old jetty.

Then I began to play hockey, and I can distinctly remember Gladys correcting my hold of the stick…right hand below left. Bill, or Bertram, eventually played county hockey with the wrong hold which, while it looked awkward, seemed to lack nothing in effectiveness.

In the summer we all showed great interest in the Children’s Sand Mission, which held services on the sands down below Julia terrace. We helped dig for and raise a pulpit and prepare sand benches in rows. We sang hymns at the bidding of the missioner, and afterwards were invited to the ground floor of a house opposite for special meditation and prayers, where I dedicated my life to missionary work among the heathen which took immediate precedence over a former choice of engine driver.

In Standard 3 I had my first fight. Bill and I were firm playmates at that time and rather fancied ourselves as a part of good full backs in the tennis ball football match played on the asphalt before being called into school. A large boy called perrott hit Bill. Here was a chance to show what I had learnt from my ‘weekly magazine’ heroes…Sexton Blake and Tinker etc. he rushed at me, arms flailing and head down, to which the correct response is a graceful side step and a left to the chin. Wish. I could report that this, indeed, happened. In fact the school ‘come in’ whistle found us both grovelling on the floor in a most undignified mix-up.

Later, I had my second and last fight. The classes were mixed and there were favourites among the girls. I believe a boy called Toogood, who I remember as a ginger headed stocky boy, pulled my current love’s hair. A fight was inevitably called for and, after school in the dinner hour, each of us became the centre of his own group of supporters and we all moved down through the town to the Coronation Field, where we soon had our coats off and sleeves rolled up., facing each other in the circle of boys…were there girls too?…I don’t know…but probably not. Egged on by the yelling supporters we bashed away at each other until there came a cry of ‘Cop’ and all the boys ran away.

Actually, I am not sure of the ‘Cop’ factor, I have an idea that it was the local curate, the Rev Kerr Thompson, for whom we all had a great respect and liking, who happened to be passing, who stopped the fight.

Other memories emerge from this period…probably about 1911 or ’12. A boy called Charlie Leadbetter and I attempted to form a boxing club, collecting pennies from those interested, for the purchase of the necessary equipment. At the back of Bob Herring’s garage we found an area large enough for a boxing ring and we spent much time erecting one with the purchased posts and rope. Sadly the project came to naught…I am not clear why, but no boxing ever took place there.

One memory of myself as a boy scout. There was some kind of ‘jamboree’ held one day during which a competition was held at fire making. Each scout had the materials for a fire and a billycan of water. At a given signal we had to get a fire going and a billycan boiling. Hodgie had come to watch the goings on. So well I remember my frantic efforts to get my fire going bowing and weeping at the same time as smoke from surrounding fires billowed up. I never got the fire going at all and collapsed in despair on Hodgie’s comforting bosom as the winner was announced.

But there were many other activities. There were hoops made by Mr Welland the blacksmith which boys and girls ran along with in the streets, marbles, and conkers hard baked for toughness, games like ‘weakhorses’ and, in the evening sometimes, ‘John O’ Lantern’ a fascinating night hunting affair across the fields, with one boy as quarry, running with a lamp which he would show, briefly, when demanded by the hunters.

I remember being sent up the street to the toyshop to buy a 2d cane in the middle of lunch, by father…some misbehaviour I expect. At this time I had developed eczema in the corners of my mouth with zinc ointment dabbed on as a relief, and I became very choosy in what I would eat, with revulsion to any meat except roast beef and Yorkshire pudding. I loathed mutton and was given beef tea soaked in bread instead. This held until after my first term at boarding school after which I would eat anything that Mother provided.

Friday afternoons in school are always remembered with pleasure, not only for the silent reading sessions but for what went before…the ‘all classes’ singing session, with ‘Longfellow’s Song of Life’, ‘hail smiling morn’ and ‘Who would o’er the Downs so free O who would with me ride’ etc.

At home, in the long evenings I would have homework to do in the sitting room behind the shop with mother working away at a huge pile of stockings and the fire burning merrily.

I had piano lessons and practiced in the cold drawing room above. Ron learnt the organ under Mr may, the official church organist, and many a boring hour I spent with him at church pumping the organ bellows in the vestry, a chore sometimes shared with me by Bill (Bertram). I suspect Ron had to fork out some little inducement in pocket money for our assistance.. Bill and I could enliven proceedings by putting pieces of paper in the large square mouths of the brass pipes and having bets on whose piece would blow out first. Our names are probably still to be seen written in ink high up at the top of the organ pipes.

Bill and I had a fort with soldiers, guns, etc, which we used to have out on the floor of the drawing room on Sundays. We played Tommies and Boers, shooting across the floor with matchsticks from the guns at each other’s defensive lines. The Boer War was still very much with us and battles like Spion Kop, for instance, were pictorially presented in lurid detail in two volumes of a publication called ‘With the Flag to Pretoria’.

One of these volumes I still possess, rescued from a jumble sale in the evening and brought back for 2d;…in Leamington Spa about 1953. I always wonder who bought the other one, and for how much. Anyway, I also still have some carefully, very carefully written poems and hymns inspired by these volumes.

Voting procedures for polling day would be at the school and I remember one wintry evening when the sea came over the wall and down the street.Uncle Edward from Ilford in London came down to vote (he owned some property in Burnham) and took me with him in a taxi up the street to the school for that purpose.

We had no spare beds in our home but room was found in the bed Bill and I shared. I remember so well waking in the night and seeing the handlebar moustache rising and falling. We used to go round singing ‘Vote, vote, vote for Mr Sandys…drive old Wellsie out of the land’ during one general election.

Saturday mornings were especially busy mornings for the shop. All weekend orders had to be delivered as early as possible and this meant to farms in Brean, Berrow, Brent and Highbridge in addition to local homes. Dad would be up at 5.30 and calling up the stairs for ‘bertram, Ahvo, Eric!’ And we would hurriedly dress and report for our loads of meat…bicycles at the ready. Well I remember one journey down to Brean when the wind was strong and the long dreary returning against the wind, which funnelled gustily between the dunes.

And after a hearty breakfast, hearing the seductive voice of Fred, filling my basket again with remarks like ‘this is for that nice lady in rectory Road who always has a nice piece of cake for you.’

And, sometimes, in the afternoon, it would be my turn to cycle down to Huntspill to fetch a load of chickens, hoping to be back in time to be on the sands with the football and the other lads, but finding, when I got to the farm, that they were still busy lucking the feathers off them and I had to wait until they had finished.

During the morning Joe or Ron would be early off down tp Berrow Road with the pony and cart, calling for orders which would be delivered on a second journey, somewhere about 11am…at about which time the telephone would ring and we would hear ‘I am Mrs Bailey from Wanganella House…when is my meat coming?’

And then dad’s mollifying, obsequious voice, ‘Yes madame it is on the way now.’ Mrs Bailey was headmistress of a large girls’ boarding school and one of our valued customers. One, at least, who helped retain the business’ cash flow by paying regularly.

The shop on Saturdays would seldom shut before 10pm and up to this time small packets of meat would be made up and sold in 2d lots in order to clear. In time, however, the doors would be closed and the blinds drawn then dad would set to and make up the pay packets for the men before they went home and we would get our pocket money, perhaps 6d, according to age.

CHRISTMAS

At Christmas there would be a special ‘Show Night’ in which all shops in the town would take part, with a prize for the best dressed shop. This would be on a Friday. Our shop would present a semicircle of carcasses, all decorated with prize labels and rosettes, and in the sitting room behind the shop would be laid out a variety of drinks for the farmers and other customers who would be invited in for a drink and a chat and, I feel ashamed to report, over the mantlepiece (this was before 1910) they read a flagrant piece of begging to ‘give something towards my bike’ which, soon afterwards, I was able to acquire for £4.

Soon afterwards came Christmas morning, and the weight of the filled stockings on our feet and the strong urge to get up before time, only to be restrained by Ron, keeping us down till 7.30. Then everyone except Hodgie, to church with ‘Hark the herald Angels SIng’… always the first hymn, and after dinner, Hodgie coming in with the spirit lit pudding…lights out first… holly on top and the ‘cooees’ and the hunt for the threepenny bits.

The long afternoon in the drawing room exploring and enjoying the delights of the presents…and the evening carol singing and, sadly, the end of another Xmas. How lucky we were with our happy home life and how much we owe to Father and Mother who made it possible.

In the 1960’s a man walked into my study at Swanage and said ‘I have good news for you sir, an insurance policy your Dad took out when you were born has matured…I have £45 for you.’ Apparently dad had, for each child, taken up a policy of 6d per week. It enabled me to buy a ‘Black Box’ gramophone which I enjoyed for many years.

STILL MORE MEMORIES

Reverting to my acquisition of a bike… in justice to myself I think I should report some effort I made toward acquiring it. This was in the disposal of tripe, of which commodity we often had a surplus. Fred proposed that I go out with bundles on a tray and sell them on commission. The butcher’s tray is now never seen; it was a very narrow tray with four handles, one on each corner, and designed to be balanced on the shoulder.

Fred suggested that I knock on the doors of the terrace between the Ring 0’ Bells (a pub at the bottom of College Street) and the Convent, offering the tripe for sale at 2d per skewers. For each unit sold I would be able to claim 12%, that is, a farthing, as commission. It seemed a good idea, the way Fred put it, but at the end of the afternoon, with 40 bundles disposed of, I found I qualified for 10d to be added to my bicycle fund which , in retrospect, hardly justified my efforts and loss of afternoon’s play on the sands. Still, by such experiences we learn and 10d then would be £1.50 now [1986].

The Convent, where Cecil, in his retirement years, found very satisfying and appreciated occupation, was well known for its hospitality, readily offered to any person that entered its courtyard and rang the bell. Tramps, who, in those days were encouraged to keep moving from workhouse to workhouse where beds could be obtained for only one night, often called at the Convent in midday for the bowl off soup they knew would be there for them. At times when I have delivered meat there, it was considered a matter of course that I would not refuse this favour and, appreciating the quality of what was offered I willingly co-operated.

Return to College St.